While Russia is a tremendous market ($1.7 billion in 2018) for gaming and there are an incredible number of Russian game developers and publishers, Russian games don’t get a lot of visibility in a gaming culture that’s focused on the US, Europe, and Japan. We’re not familiar with the Russian perspective and storytelling tradition, particularly since Russian genre fiction is tricky to get ahold of.

There have been occasional breakouts like Night Watch and the science fiction of Stainslaw Lem, but otherwise we’re left with the Cold War hangover of Russia as the land of Bad Guys and Good Accents or the modern perception of Putin riding a bear and making the President of the United States do his silly monkey dance.

Metro 2033 provided a portal into that culture. American-European narratives of nuclear apocalypse tend to be Great Man-focused, with a noble hero setting out to solve problems and survive or with him–it’s usually a him–grimly facing down the inevitable end of all things. The US and her European allies spent a lot of time creating the impression that nuclear apocalypse was survivable. Reading Civil Defense manuals and plans from the 80s is like a monologue from General Turgidson in Dr. Strangelove: Sure, we might get our hair mussed… Western games tended to be along the same lines. The post-apocalyptic Fallout world might be weird and unsettling, but humanity survived to rebuild and make the same mistakes it made the first time.

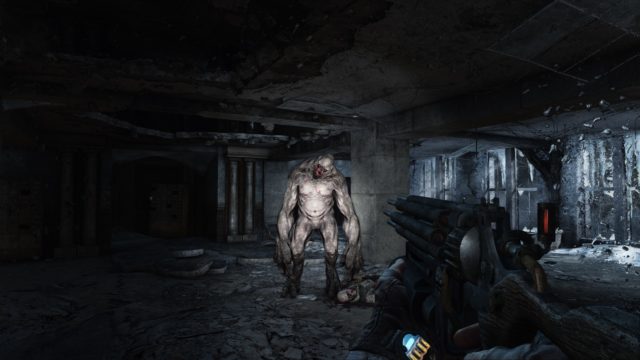

The Metro series gave us a bleak world where survivors cling to a perilous existence in the remains of the Moscow metro system. This makes us travelers in an alien world. For children of the Cold War, we may not have even known Moscow had a metro system, much less one sheltering survivors in a nuclear exchange. It was a familiar sensation–the subway–but alien–the subway built by people we didn’t really know.

Maybe the real alien portion was exploring a distinctly different set of values from the values we’re used to encountering. The game had a couple different endings, but didn’t obviously push you into one or the other. You could help the homeless and needy and build up to the “good” ending, but there was very little push to do so.

Some players got through the game not realizing there was an alternate path at all. It was a far cry from a Bioware-style “I am the Ayn Rand ubermensch and you are unworthy scum” vs. “I am basically Jesus and Ghandi combined” morality system.

And it was scary as hell encountering mutants in the dark, trying to manage your resources and mask, and just trying to push through and see what the hell was going on. Western games love to revel in darkness and weird, but nobody does hopeless, helpless darkness like the Russians.

Metro: Last Light brought us back to the irradiated world of metros and mutants, but it also brings us back to the past. Nazis–it may have seemed laughable for Nazis to come back, but in 2019, we have to call them “white nationalists” or they get their feelings hurt–and Soviet throwbacks play a much larger role than they did in the first game, as the player chases rumors of a pre-war bunker full of riches.

While sticking us in the future, it’s mostly a game about the past, with the player character pondering their actions in the first one, fighting the ghosts of World War II, and dealing with the consequences from 2033. In the “good” ending, there is a modicum of hope, but just a small one. Humanity is still stuck on an irradiated planet full of mutants, but it may get better. Someday.

There’s an irony that the newest installment brought about an apocalypse of its own by announcing exclusivity on the Epic Store and getting buried under a tide of angry gamer outrage. Will we find out what happens? Will the series survive? Is the new one actually any good? Does it matter if the corrosive radioactivity of modern gaming buries it?

Pingback: Metro Exodus Review - Get in, Loser, We're Going to Find Humanity | MonsterVine